My latest posts can be found here: Previous blog posts:

Additionally, some earlier writings: |

This page has been

Tagged As Maths One formulation is to say that the product of non-empty sets is always non-empty, and that sounds so obvious. Let's see what this leads to ...

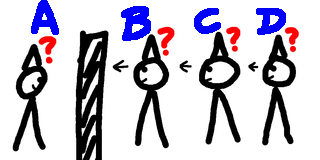

A Four Hat Problem.There are several formulation of this one.

The fourth person is in a separate room. No one can see their own hat, but each person can see the hats of anyone in front of them. Remember, two hats of each colour. The people are challenged to announce the colour of their own hat. If someone succeeds, they all get rewarded handsomely and released from this bizarre situation. But it must be the first thing they say, and the consequences of getting it wrong are unspoken, but dire. Can anyone work out the colour of their hat?

A hint ...Silence is a clue ... A solution is later.

Another Hat Problem.Now suppose we have 100 people in a row, all facing forward, all wearing a hat that's either black or white. Each one, starting from the back, is asked their hat colour. They announce it loudly enough for everyone to hear, and the others also hear whether they got it right or wrong. How many can we save? We can easily save half the people by having the odd-numbered candidates announce the colour of the person in front of them, and the even-numbered ones repeating that answer. If the hats are random then we can save about 75%, but maybe we can do better ... Yes we can ... the answer appears further down the page.

Meta-analysis ...In each of these cases the "contestants" are gaining information by being able to hear other people's responses. So people can somehow encode information for others to act on, and we can save more than the average "half". But what if people can't hear what others say? There is still hope. Even if people can't hear what others say, people can pair off, and each then looks at their partner's hat. One can say the colour of their partner's hat, and the other can say the opposite of their partner's hat. Now even if they speak simultaneously, or if they are taken out an asked when no one can hear what they say, nevertheless we are guaranteed to save exactly one of each pair ... you might want to see why that is true. Hmm.

Infinitely many people ...There are many, many variants of hat problems, but this has set the scene, so I'll jump straight to the version of interest. We have countably many mathematicians who are all blessed with an infinite memory. They are told what will happen beforehand, so they can all discuss their strategy, and then commit it to memory. And here's what will happen. They will be brought into a room, one-by-one, and given a sequence number as they go, starting with 1 and including all the positive integers. As they enter the room a coin will be flipped (although the administrator might cheat!) and that determines whether they get a black hat or a white hat. Communication is forbidden, but each person can see everyone else, both their number and the colour of their hat. Then, one by one, in sequence, they are taken back out of the room and asked the colour of their hat. If they are right they are released. If they are wrong they are incarcerated forever. And no one in the big room knows the fate of those who go before. So think about that for a bit. Each person has no information about the hat on their own head, and they gain no information for the answers of the others. The only information they have is the colour of everyone else's hat.

The situation seems hopeless. Read on ...

Solution to the Four Hat Problem.

In each case, someone can announce a hat colour.

The Hundred Hats Solution.In this case we get the first person to count how many white hats they can see. If it's even they say "White", otherwise they say "Black". They have a 50:50 chance of surviving/winning. Bue the next person now knows the parity of the remaining number of white hats. They count the white hats and if they get the same parity then they know their hat is black, otherwise they know their hat is white, and in either case they act accordingly. Each person can keep a running total of what's happening, and so, provided they don't make a mistake, they can all save themselves. And even if someone makes a mistake, the others can detect that it happened and adjust accordingly. So all but the first person is guaranteed to be saved (provided they don't make a mistake), and the first person has a 50:50 chance. Not bad.

And now, infinitely many mathematicians ...Back now to our infinitely many mathematicians with the randomly assigned hats. It seems impossible to do better than just 50:50 for everyone. If each can hear the answer of the one before then we can save all the even numbered people. In fact, we can "chunk" people into groups of 100 and save 99% of them. Or more! But that requires being able to hear the answers. If we can't hear the answers, the situation seems hopeless. But it isn't. There is a strategy to guarantee saving all but finitely many. Even though the hat assignment is random, and no one can hear anything anyone says, we can guarantee saving all but finitely many.

Axiom Of Choice to the rescue ...Here is one strategy ... I'm sure there are others.

Take another sequence, put that in another bucket, and do the same. Then again. And in fact, define buckets such that each bucket has sequences that differ in only finitely many places, and every sequence is in some bucket. The collection of buckets is a collection of non-empty sets. So by the perfectly reasonable Axiom Of Choice we can select one item from each bucket. This is our "Choice Set", and all of our mathematicians commit to memorising it. Now move forward in time to when we are in the room. The sequence of hats we can see was in one of the buckets, and from that bucket we have selected a particular "Chosen One". What's more, everyone knows which one it is. So now everyone, in their own mind, has the same chosen sequence, and that chosen sequence only differs from the sequence in the room at a finite number of places. So all the mathematicians call out, at their appointed time, the colour designated by the chosen sequence. And all but finitely many will be saved.

Conclusion?There are, of course, a few possible objections to this. For one, look at how many buckets there must be, wonder about the ability of the mathematicians to remember all this information, and so on. But even with all that, the very possibility that the Axiom Of Choice might let us do this should raise some serious concerns. This isn't the only "paradoxical" result

Send us a comment ...

|

Suggest a change ( <--

What does this mean?) /

Send me email

Suggest a change ( <--

What does this mean?) /

Send me email